Notes from Donald Carmichael (1901 – 2003)

As a child, I grew up in Port Appin and was the eldest of seven, with my 3 brothers and my 3 sisters, living at Seaview, a two-bedroom apartment on the road to the pier.

My father, Sandy (born 1867) had several jobs, though his main occupation was a shoemaker. Before he married, he left the Isle of Lismore to learn his trade with the Cunningham relations in Barcaldine.

At Seaview, he used the room to the roadside that looked down towards the pier. The room had two windows and provided the best light for working. It was also a regular meeting place, where we used to gather, while my father was working. The hide was ordered in and the best of the leather was cut from it and then steeped in water. From an early age, I would help my father, beating the leather with a mallet, over my knee. The shoes were hand sewn, soled and heeled for £2 6d.

Though my father was a shoemaker, we were no different from the other children, at Port Appin and went without shoes until the winter months. I clearly remember, as a child, running passed Airds Hotel barefooted; no tarred roads then, of course.

My father also worked as a woodman, at the timber sawmill at Glaicheriska and Airds orchard gardens. The average pay was £1 per week, less one shilling for insurance.

Robert Grieves, of the Gardens Cottage would stand at the garden gates and with his pocket watch in hand, he would clock everyone, at 7 am.

My father was very friendly with the pier master Sandy McLachlan, at Cliff Cottage. The two would visit one another, taking a path over Clach Thoul. Sandy’s brother [Donald] lived on Sheep Island and was the last person to work the lime kilns there.

Another friend of his was Dougie MacFarlane, the Lismore ferryman. The Lismore ferry at that time was just a rowing boat but fitted with a sail. The ferry fee was 6d, to cross.

I remember going over to Lismore on the ferry, with my father, to visit my grandfather, Donald Carmichael. He lived at number 8 Port Ramsay and was an elderly man at that time, born in 1814. I recall that he had a long white beard and walked with a limp, from when he broke his leg, years earlier and was set wrong. He died in 1908 at the age of 93.

Dougie Macfarlane had an arrangement with the passing paddle steamers as they headed for Fort William. He would stand at the end of the pier with either one arm extended upwards or both. One arm raised meant, ‘drop off one bottle of whisky’ on the return journey and both arms were for two bottles’!

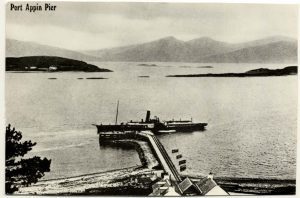

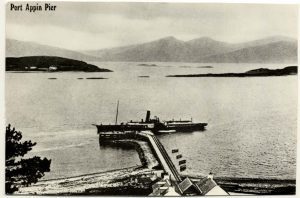

The paddle steamers passed Port Appin 5 times daily, sailing Loch Linnhe from Oban to Fort William. The Grenadier, Mountaineer and the Fusilier were among those steamers, carrying passengers, luggage and cargo. Some years later in 1927, my father-in-law, who was a police sergeant in Oban at the time, was on duty the night the PS Grenadier went on fire, at the North Pier.

When the steamers stopped at Port Appin, Dougie MacFarlane would collect a pier-due from each passenger disembarking, at a cost of thrupence. On one occasion a woman, wishing to come ashore had no money. As an exchange of payment, she gave Dougie a pair of shoes. They lay at the Pier House for years afterwards.

At times there were so many passengers, leaving the steamer to walk up to Port Appin Shop, that there would be two queues, with the first off the steamer, meeting the last disembarking.

Timber was also brought into Port Appin by the steamers for joiner, John Black. Tom Wilson from Taychreggan uplifted the materials and delivered them by horse and cart, to Tynribbie.

The coal puffer came to Port Appin twice a year and it was always a great day of excitement when it arrived. The

Many years later, my brother Jock, ran the coal business, while living at Rock Cottage. He also ran Port Appin Shop during WW2 and the butchery. Between the hall and the old school is where he kept the sheep, before slaughtering. It was known as Jock’s field.

The original water supply for Port Appin was collected at the bottom of the field, below Hazelwood. It was beautiful water that sparkled. There was a path from the roadside, down the field to the well, until it was eventually ploughed over. The well should still be there.

I remember another source of water was found in the grassy area in front of the old ferry cottages, known as the Green and a hand pump was installed, for all to use. As kids, we would carry buckets of water back to the house and was also where we often played.

Years later I dug, by hand, a water track from that pump, down to the Pier House; it was the supply for a long

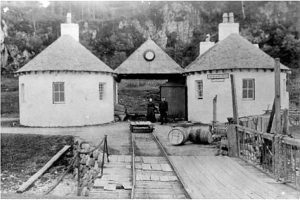

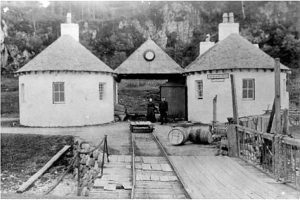

Another place we used to play was down at the quartz quarry, passed the Pier House, towards Clach Thoull. Rails ran from the quarry down to the pier, for loading the boats. We would take turns in the bogie, riding it down to the pier.

The Pier House also had rail tracks that ran down the slipway, for convoying goods to and fro the steamers. Years later, I concreted from the roadside down to the pier. Though it’s been extended to the side, the original concrete work is still visible.

Back then, the Pier House was split in two. To the left was a store and to the right was a house, where Alex MacLachlan lived, before moving to Cliff Cottage. In the centre was an open storage area, with a clock up above. At one time, it was also the Post Office, where my sister Jessie worked. In the 1910s, the post office moved up to the shop.

Past the Pier House were the fishermen’s huts [towards Clach Thoull] and dances were held there every Friday night, starting at 8 pm until one or 2 in the morning. The tailor, Alexander MacLean from Achosrigan, provided the music with his fiddle. During the dances, there would be an interval for tea and a basket of scones were passed around.

As kids, we would walk up to Tynribbie to see if there were any cars passing through the village. We would walk on the Port Appin road and those from Airds and Glaiceriska would walk along the avenue, to the Thrupenny Bit [Airds Lodge]. There was a large white stone, just further up the road and that was our meeting place. I think the county men may have moved the stone some years ago.

If MacFie of Airds House ever passed in his motor car, we would need to stand to the side of the road and salute, as he drove by. We were told that if we didn’t do so, our father could lose his job.

One time I went for a walk up to the Jubilee Bridge, where I met another kid called Billy Hamilton. He let it be known that he wasn’t pleased to see me, only because I came from Port Appin!

My first teacher at Port Appin School was Miss MacGlashan. She was a very nice and well-respected person, and

also the first appointed teacher of Port Appin School. Her father was a gardener and lived at the Gardeners Cottage. Janet Ann MacGlashan moved to Port Appin and lived with her father after her mother died and took up the post of headmistress of the new school [1890]. After he died, she moved into the schoolhouse; she was the only person ever to use the house for its intended use.

She didn’t always keep well and Flossy Macintyre of Linnhe House would stand in for her. Flossy was a former pupil at Port Appin and had advanced to the senior class at Strath of Appin School. Later, her sister, Annie became the permanent school teacher.

On the last day of Port Appin School, Jock [younger brother] threw his school satchel in the air, at the top of the school brae, saying, “I won’t need this again”. The school bag snagged on one of the tall trees opposite Port Appin Shop and hung there for years afterwards.

The school was also used to conduct church services every Sunday evening at 6 pm. The services were well attended and you had to be there early enough to have your usual seat.

There was no musical organ but Robert Grieve was the presenter. He would hit a tuning fork over his knee to find the right key, before beginning to sing the hymns.

One evening there was a woman sitting in front of me wearing a large hat and I adjusted my seating position to avoid it. The minister Rev. Ross must have thought I was moving out of sight from him and said, “You don’t need to move! If I can’t see you, God can!”

My favourite pastime was in the boat fishing for cuddies, at the Port Appin rocks and would be out every evening, if I could. The worst thing I could be told was that I wasn’t allowed to fish at the rocks. I knew the area so well and if I could see the seabed, I would know exactly my whereabouts from that alone.

I was with my father when he was talking to the blacksmith [Campbell], who was home on leave during the Great War. He was telling my dad that he would get terribly homesick and often wished he was back home and out fishing for cuddies.

Shortly afterwards, my father fell unwell and was confined to bed, at Seaview. His condition worsened and though the doctor advised that he needed rest, it was nearly impossible, as there were so many folks from Appin and Lismore calling in; everyone was concerned for him.

On 2nd March 1915, the doctor was called for again. I remember the round table in the parlour was set with a green cloth and the dresser had biscuits and a large wedge of cheese, for the visitors. The doctor asked for everyone to be very quiet and a short while later my father suffered a nosebleed and then suddenly passed away.

The time was 10.20 am and though I never talked much about my father’s death, I hated that time for many years after. In fact, I still think about it to this day. He was only 48. It is strange, reflecting back, as I thought at that time he was an old man.

I had just had my 14 birthday, exactly one week before my father died. I was the eldest of 7 siblings, with the youngest just 7 months old [Nicol].

As was the custom at the time, the curtains were drawn in the house, while preparations were made for the funeral. We received a telegram from our uncle Dugald Carmichael, from Salen, Lismore and I was told to meet the paddle steamer. I collected a delivery of two 10 stone sacks, containing oatmeal and flour.

Being the eldest child, I was asked to deliver the letter invitations for the funeral service. I cycled throughout the village, to hand-deliver them.

The service and burial were on Lismore but that day the weather was inclement and the minister was unable to attend. Our uncle Dugald, who was an elder of the church in Lismore, conducted the funeral service, for his own brother. The school was closed for the day.

It was necessary for me to leave Port Appin School and start work, to help provide for my mother and brothers & sisters. I wasn’t allowed to leave straight away and had to go back, after my father’s funeral, for another 3 weeks.

Seaview was a tied house, owned by the MacFies of Airds and without my father working on the estate, we had to leave our home. We managed to find accommodation at Barriemore [Ardtur Cottage] and the family moved there, shortly afterwards.

Some of our Lismore relatives offered to take a few of us over to live with them, to help the situation with my mother but she didn’t want the family split up.

However, I did spend some time over on Lismore with my uncle Dugald, at Salen and he became somewhat of a

fatherly figure to me.

He was known (in Gaelic) as ‘Dugald of the lime’ and was my father’s eldest sibling.

I remember the lime kilns working at Salen and the rock blasting on the cliff face, behind the kilns. The workmen wore handkerchiefs over their mouths, to stop their lips from burning while wheelbarrowing the lime down to the smacks [sailing boat with a cargo hold]. Allan MacFadyen, my uncle from Port Ramsay, sailed the ‘Mary & Effie’.

Dugald was very keen that I would take over the lime kilns when he retired but it wasn’t some

thing I wanted to do.

Dugald kept Leicester sheep at Salen. I remember he would have a ball of oatmeal in his pocket and the sheep would come to him and feed from his hand.

My uncle had butter churns and would make enough butter to last the winter. He was very particular about the cleaning of the churns and wouldn’t let anyone else clean but himself.

He was also the coal merchant and brought the coal in at Port Ramsay. Though he had a good understanding of English, he would count in Gaelic and then translate.

I was the only young person at Salen, amongst the older workmen and there wasn’t much to do after work was finished for the day. I would sometimes walk around by the shore to the cave and spend time there. It was, at one time, where two brothers built boats.

Every Sunday we walked from Salen to the parish church, for the morning service. Afterwards, we would spend the afternoon at Clachan, with the Black’s and then go to the evening service, conducted in Gaelic.

While living at Ardtur Cottage I began working for the Russell Fergusons, of Ardtur House. I was able to bring some income home to help my mother and like my father before me, worked as a shoemaker.

I remember my mother with long auburn hair, that was pleated and she was slightly deaf. She worked hard in the garden, at Ardtur Cottage and grew all her own vegetables, not believing in tinned food.

We often walked with my mother [Jane-Ann, born 1874] around Clach Thoull and the cats would follow us as far as The Croft road-end before then returning home.

Our neighbours at Ardtur were Sam and Mary MacColl, from The Croft. Mary was very friendly with my mother and looked out for us; we often received milk and butter from them.

A steady part of our diet was rabbit and I knew every burrow where I could set a snare. However, I wasn’t allowed to set traps on the side of Ardtur House, but only across the road, on the windmill side [a windmill was installed to pump water to Ardtur House].

The Russell Ferguson’s kept bee hives, at Ardtur and it was there my own interest in beekeeping came. For many years I kept hives, as did my three brothers.

While working for the Russell Ferguson’s, I planted the whole area of the large knoll, next to the road that leads to Ardtur Farm; the trees that you see today. On the other side of the farm road was the golf course [Appin Links].

My brothers also work under the employment of the Russel Ferguson’s, on the estate grounds at Ardtur.

Jock later worked at Airds Hotel, when owned by the MacGregor’s of Mull and would collect and drop off guests that travelled by train, to Appin Station. His passengers and luggage were transported by a two-horse-drawn waggonette that would carry 4 to 5 people, to and from the station. Single passengers were collected by the pony and trap. If the tide was out or at a low enough depth, from Cuildhu he would cut across Loch Laich, following the pole markers that indicated the hardstanding [one pole still remains today].

I also used a pony and cart, while at Port Appin. The retired policeman who lived at Tigh na Drochaid, taught me how to cut and stack peat, on the road leading up to the Gardeners Cottage. When the cart was loaded, I would lead the pony up to Ardtur Cottage.

Across the road at Dalnashian, an extension was being built by the contractor John McLaughlin, of Oban. I remember being up on their timber scaffolding and it was from there that my interest in building came. Later I started work with Ferguson Builders in Ballachulish and a new chapter began.